Massively Parallel Programming

Embrace the capabilities of AI-native coding

I started my career as a data scientist intern at a startup called Bundle. One of my projects was building some servers and setting up a small in-office Hadoop cluster to speed up recurring data ingestion jobs.

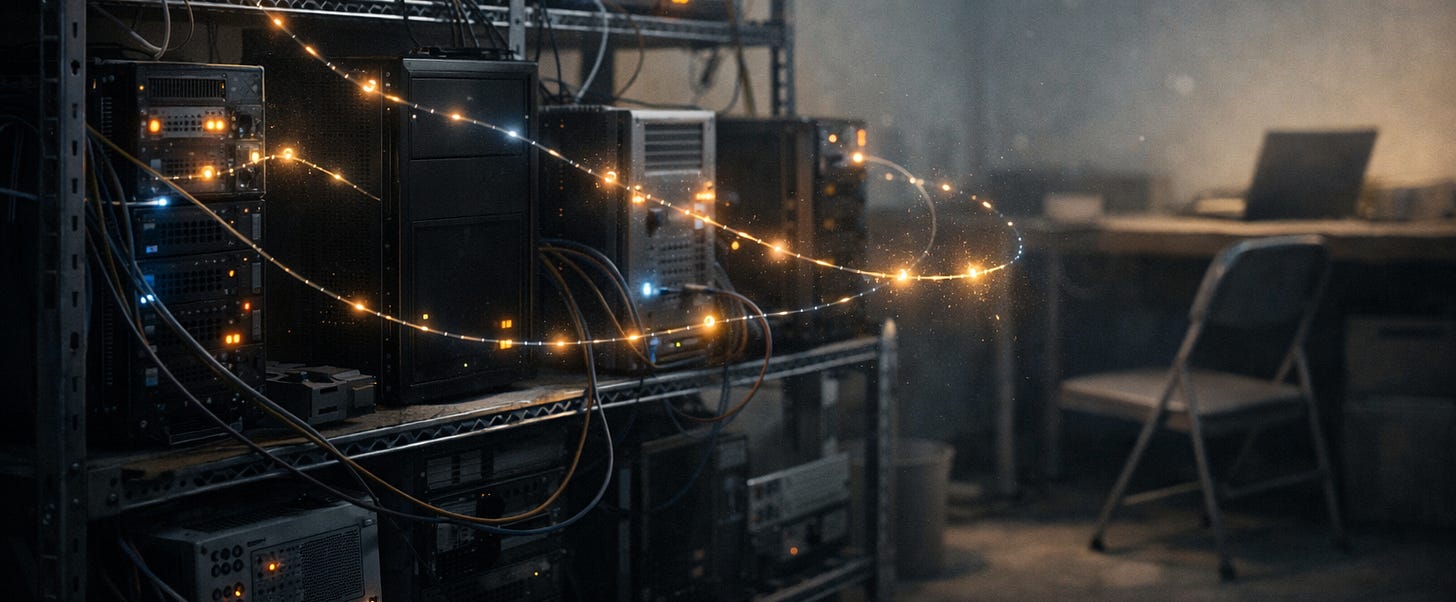

If you’re not familiar with Hadoop, it’s a framework/ecosystem for doing Massively Parallel Processing. This is a paradigm that has been around for decades that started getting very popular in the mid 2000’s to power the data processing jobs that let web companies scale to billions of users. The same distributed principles power the large GPU clusters used to train AI models.

At a high level the way it works is you break up a large job into small tasks that can be executed independently, and then coalesce the results back together into a final output. A key property of these frameworks, and what distinguishes them as “massively” parallel, is not just that they can handle larger amounts of data. It’s that they are designed to be robust and self-healing. Rather than hoping nothing goes wrong, or trying to recover from every error individually, they’re designed to succeed even when things do go wrong. Servers in the cluster can crash or go offline, and their work can just be routed elsewhere and completed successfully. When that happens sometimes chunks of work are abandoned partway through, or get done twice, but it’s fine, one of them is thrown out and the system keeps moving along. When a server recovers and comes back online, it rejoins the cluster and picks up the next task as if nothing happened.

When you’re working with these systems you can mostly look at a job that ran and see a successful result, and that’s all you have to care about. The detailed logging is available if you ever do need to dig in to the details of what happened on a particular node for a particular chunk of the task, but you rarely need to. You focus on what you put in and what you get out, and trust that the system will figure out the part in the middle and make it all work even if things don’t go perfectly.

A new paradigm for programming

I think we can learn a lot from these systems in designing new programming workflows for the world we now live in.

If you’ve done a lot of LLM coding, you’ve probably experienced this common trajectory. First using an in-editor tool like Cursor, where you’re mostly following along as if you were writing the code, except the LLM is making the changes. Then moving to Claude Code or Codex, where you interact with the CLI and don’t even need an editor open. The agent is flying along and once in a while you notice it going down the wrong path and try to jump in with ctrl+c before it can mess things up too much. After a while, just watching one scrolling terminal doesn’t feel very efficient. So you open up 3 or 4 sessions. Then you’re frantically toggling back and forth, scrambling to give them new directions fast enough to keep the runaway slop at bay.

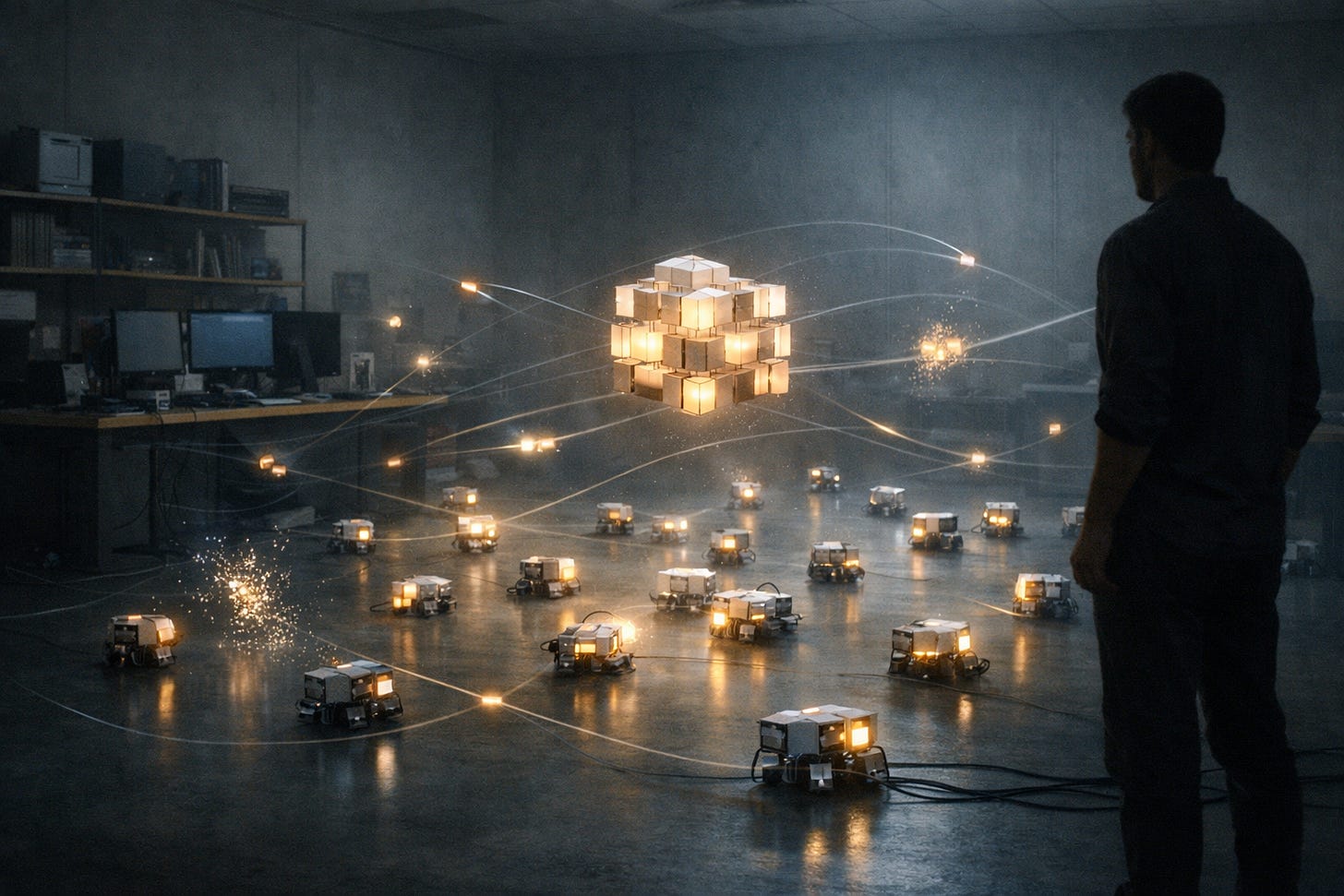

Maybe you think you need new keyboard shortcuts for tmux to be able to view them all in one screen, or dashboards to keep track of all the sessions. But distributed systems don’t work because someone is watching them closely. They work because they’re built so that no one has to.

That’s the idea behind Massively Parallel Programming.

Rather than staying deep in the weeds trying to understand every change as it happens, take a step back. Focus on the inputs and outputs and let the system of agents handle everything in between. Yes, they’ll make mistakes. They’ll go down wrong paths. They’ll put logic in places that don’t make sense. But if they come up with a fully working system that passes all acceptance criteria and testing harnesses you’ve defined — then does it matter? You have a fully working feature, that you can ship today. Isn’t this inevitably what every real world codebase looks like anyway? A ball of mud where anyone looking at it with fresh eyes wonders “what were those original engineers thinking?” But it’s getting the job done and working to solve the problem it was created for. And of course, you can always use AI to refactor it once it’s working. The AI giveth slop and the AI can help un-slop.

I’m not suggesting we don’t read any code at all, just that we don’t have to read it all in real-time. Certainly not as it’s being written, and, dare I suggest something this heretical... maybe not even as it’s being reviewed and shipped? Yes, it sounds like a completely irresponsible thing to say. But I honestly don’t see any other way this plays out. The agents have gotten too good. The teams that are most competitive and able to move fastest will likely be the ones that can remove humans as the bottleneck.

What should our relationship to codebases look like, then? It’s definitely still an open question that we’ll all be trying to figure out in the coming months and years. We’re still responsible for any bugs and outages that get shipped on our watch, so we’ll have to find ways to be confident we can prevent them. Documentation is obviously important, and diagrams of control flows and important interactions in the app. I think better tools to help visualize and understand codebases will be very useful, as a high-bandwidth way to get an overview of they work. We should also definitely still dive in and read the code, but maybe this becomes something we do in batches. Do deep dives in specific areas as they become important/relevant to you. Have interactive discussions with LLMs to understand them quicker as you read.

One last point to add — there’s a big opportunity in all of this to overhaul how we think about testing and make our releases much safer and more predictable to help offset any added uncertainty from AI tools. No company I’ve ever worked at has been completely happy with their testing practices. QA teams are under-funded. Unit test coverage is a little bit lower than you want it to be. End to end tests are flaky or missing coverage when new features are added. Testing for data races, or fuzz testing randomized inputs may exist only sporadically. Load testing is often only done ad-hoc and not systematically. We should absolutely be raising the bar on the level of test coverage we accept. The interesting tie-in to Massively Parallel Programming is that not only does more comprehensive test coverage make our systems more reliable, it makes the coding phase require less human intervention since agents can keep running until all the tests pass.